Mediterranean diseases

Leishmaniasis

What is Leishmaniasis (leishmania)?

Leishmaniasis is a mediterranean disease transmitted to dogs by a tiny sandfly. The sandfly is active between dusk and dawn and is common in all Mediterranean Countries, (unfortunatley as climate change increases we will be seeing more cases of sandfly over in more and more contries). When an infected sandfly bites a dog, the dog is in danger of contracting the disease, unless it is protected by an insect repellent collar, called a ‘scallibor’ collar.

Leishmaniasis is a mediterranean disease transmitted to dogs by a tiny sandfly. The sandfly is active between dusk and dawn and is common in all Mediterranean Countries, (unfortunatley as climate change increases we will be seeing more cases of sandfly over in more and more contries). When an infected sandfly bites a dog, the dog is in danger of contracting the disease, unless it is protected by an insect repellent collar, called a ‘scallibor’ collar.Leishmaniasis, the medical term used for the diseased condition that is brought about by the protozoan parasite Leishmania, can be categorized by two types of diseases in dogs: a cutaneous (skin) reaction and a visceral (abdominal organ) reaction – also known as black fever, the most severe form of leishmaniasis.

The infection is acquired when sandflies transmit the flagellated parasites into the skin of a host. The incubation period from infection to symptoms is generally between one month to several years. In dogs, it invariably spreads throughout the body to most organs; renal (kidney) failure is the most common cause of death, and virtually all infected dogs develop visceral or systemic disease. As much as 90 percent of infected dogs will also have skin involvement. There is no age, gender, or breed predilection; however, males are more likely to have a visceral reaction.

The main organ systems affected are the skin, kidneys, spleen, liver, eyes, and joints. There is also commonly a skin reaction, with lesions on the skin, and hair loss. There is marked tendency to hemorrhage.

Symptoms and Types

There are two types of leishmaniasis seen in dogs: visceral and cutaneous. Each type affect different parts of the dog’s body.

-> Visceral — affects organs of the abdominal cavity

- Severe weight loss

- Loss of appetite (anorexia)

- Diarrhea

- Tarry feces (less common)

- Vomiting

- Nose bleed

- Exercise intolerance

-> Cutaneous — affects the skin

- Hyperkeratosis — most prominent finding; excessive epidermal scaling with Alopecia — dry, brittle hair coat with symmetrical hair loss

- Nodules usually develop on the skin surface

- Intradermal nodules and ulcers may be seen

- Abnormally long or brittle nails are a specific finding in some patients

-> Other signs and symptoms associated with leishmaniasis include:

- Lymphadenopathy — disease of the lymph nodes with skin lesions in 90 percent of cases

- Emaciation

- Signs of renal failure — excessive urination, excessive thirst, vomiting possible

- Neuralgia — painful disorder of the nerves

- Pain in the joints

- Inflammation of the muscles

- Osteolytic lesions — a punched-out area with severe bone loss

- Inflammation of the covering of bones

- rare : fever with an enlarged spleed (in about one-third of patients)

Please protect your dog against the sandfly. Use a Scalibor collar for you dog. If you notice from your dog one of the signs, please go to the vet and let them treat your dog. Leishmaniasis leads untreated to death! Without treatment your dog suffers anguish and pain. So help your dog. He can not help themselves.

Diagnosis

Your veterinarian will perform a thorough physical exam on your dog, taking into account the background history of symptoms and possible incidents that might have led to this condition. A complete blood profile will be conducted, including a chemical blood profile, a complete blood count, and a urinalysis. Your doctor will be looking for evidence of such diseases as lupus, cancer, and distemper, among other possible causes for the symptoms. Tissue samples from the skin, spleen, bone marrow, or lymph nodes will be taken for laboratory culturing, as well as fluid aspirates. Since there are often related lesions on the skin’s surface, a skin biopsy will be in order as well.

Most dogs with leishmaniasis have high levels of protein and gammaglobulin, as well as high liver enzyme activity. Even so, your veterinarian will need to eliminate tick fever as the cause of the symptoms, and may test specifically for lupus in order to rule it out or confirm it as a cause.

Treatment

Leishmaniasis can not currently be cured, but it can be treated. A dog with leishmaniasis can live a happy and healthy life for many years. The usual treatment is with Allopurinol tablets, which are cheap and readily available as they are used for treatment of gout in humans.

The sooner the condition is diagnosed, the more successful the treatment is. An owned dog, who is well fed and nourished, is of course likely to respond to treatment better than a stray dog who lives on scraps scavenged from the streets.

You can routinely treat infected dogs rather than euthanise them.

Unless your dog is extremely ill, it will be treated as an outpatient. If it is emaciated and chronically infected, you may need to consider euthanasia because the prognosis is very poor for such animals. If your dog is not severely infected, your veterinarian will also prescribe a high-quality protein diet, one that is designed specifically for renal insufficiency if necessary.

This is a zoonotic infection, and the organisms residing in the lesions can be communicated to humans. A transmission to humans is very unlikely and also never been proven.

The organisms will never be entirely eliminated, and relapse and requiring treatment is inevitable. Your veterinarian will advise you on the best course with medication.

Living and Management

Your veterinarian will want to monitor your dog for clinical improvement and for identification of organisms in repeat biopsies. You can expect a relapse a few months to a year after the initial therapy; your veterinarian will want to recheck your dog’s condition at least every six months after completion of the initial treatment. The prognosis for a successful cure is very guarded.

All our dogs are tested for mediterraniean diseases, but please ensure your dog is kept fit and healthy by taking him/her to the vet every year for a full check up. The disease can go unnoticed for a very long time.

Canine ehrlichiosis

What is canine ehrlichiosis?

Ehrlichiosis is a tick-borne infectious disease of dogs.

The organism responsible for this disease is a rickettsial organism. Rickettsiae are similar to bacteria. Ehrlichia canis is the most common rickettsial species involved in ehrlichiosis in dogs, but occasionally, other strains of the organism will be found, i.e., Anaplasma platys (formerly Ehrlichia platys), Anaplasma phagocytophila (formerly Ehrlichia equi) and Ehrlichia ewingii.

How is a dog infected with Ehrlichia?

Ehrlichiosis is transmitted to dogs through the bite of infected ticks. The brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, is the main carrier of the Ehrlichia organism in nature. Other tick species, particularly Ixodes (A. phagocytophila), Amblyomma and Otobius (E. ewingii) have also been shown to transmit Ehrlichiosis in dogs.

transmitted to dogs through the bite of infected ticks. The brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, is the main carrier of the Ehrlichia organism in nature. Other tick species, particularly Ixodes (A. phagocytophila), Amblyomma and Otobius (E. ewingii) have also been shown to transmit Ehrlichiosis in dogs.

What are the signs of Ehrlichiosis?

Signs of Ehrlichiosis can be divided into three stages:

- acute (early disease),

- sub-clinical (no outward signs of disease),

- and chronic (long-standing infection).

- In areas where Ehrlichiosis is common, many dogs are seen during the acute phase. Infected dogs may have fever, swollen lymph nodes, respiratory distress, weight loss, bleeding disorders, and, occasionally, neurological disturbances. This stage may last two to four weeks.

- The sub-clinical phase represents the stage of infection in which the organism is present but not causing any outward signs of disease. Sometimes a dog will pass through the acute phase without its owner being aware of the infection. These dogs may become sub-clinical and develop laboratory changes yet have no apparent signs of illness. The sub-clinical phase is often considered the worst phase because there are no clinical signs and therefore it goes undetected. The only hint that a dog may be infected during this phase may be after a blood sample is drawn, when the dog shows prolonged bleeding from the puncture site. A low platelet count (called thrombocytopenia) and/or hyperglobulinemia (high levels of globulin in the blood) may be found incidentally on laboratory tests. Dogs that are infected sub-clinically may eliminate the organisms or may progress to the next stage, clinical Ehrlichiosis.

- Clinical Ehrlichiosis occurs because the immune system is not able to eliminate the organism.

- Dogs are likely to develop a host of problems:

- anemia,

- bleeding episodes,

- lameness,

- eye problems (including hemorrhage into the eyes),

- neurological problems,

- and swollen limbs.

- If the bone marrow (site of blood cell production) fails, the dog becomes unable to manufacture any of the blood cells necessary to sustain life (red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets).

- Dogs are likely to develop a host of problems:

How is Ehrlichiosis diagnosed?

It may be difficult to diagnose infected dogs during the very early stages of infection. The immune system usually takes two to three weeks to respond to the presence of the organism and develop antibodies.

It may be difficult to diagnose infected dogs during the very early stages of infection. The immune system usually takes two to three weeks to respond to the presence of the organism and develop antibodies.

Since the presence of antibodies to Ehrlichia canis is the basis of the most common diagnostic test, in the early stages of disease dogs may be infected yet test negative. Testing performed a few weeks later will reveal the presence of antibodies and make confirmation of the diagnosis possible.

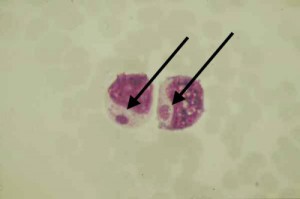

Rarely, the organism itself may be seen in blood smears or in samples of cells taken from the lymph nodes, spleen, and lungs. This is a very uncommon finding. Therefore, detection of antibodies, coupled with appropriate clinical signs, is the primary diagnostic criteria.

A newer test, a PCR assay, is becoming available in certain veterinary laboratories. If a dog is suspected of having Ehrlichiosis, this test should be considered.

How is Ehrlichiosis treated?

Dogs experiencing severe anemia or bleeding problems may require a blood transfusion. However, this does nothing to treat the underlying disease.

Certain antibiotics are quite effective, but a long course of treatment, generally six weeks, may be needed. Your veterinarian will discuss treatment options with you.

Can anything be done to prevent Ehrlichia infection?

Ridding the dog’s environment of ticks and applying flea and tick preventives are the most effective means of prevention.

Can I get Ehrlichiosis from my dog?

No. However, humans can get canine ehrlichiosis from tick bites. The disease is only transmitted through the bites of ticks. Thus, although the disease is not transmitted directly from dogs to humans, infected dogs serve as sentinels to indicate the presence of infected ticks in the area and may be a source of the organism for infections in humans or other dogs.

Please protect their dog with spoton preparations or tick collars (best is Scalibor – this also protects against sandflies) from the bite of a tick.

Please protect their dog with spoton preparations or tick collars (best is Scalibor – this also protects against sandflies) from the bite of a tick.

If you find a tick on your dog please remove it immediately.

If your dog shows one of the described signs of disease, please go to the vet. Ehrlichiosis can lead untreated to death.

Babesia Infections

What is a Babesia infection?

Babesia infections occur in dogs and other species, and are transmitted mainly by ticks. Babesia are protozoal parasites that attack blood cells, though the severity of illness varies considerably depending on the species of Babesia involved, as well as the immune response of the infected dog.

Babesia infections occur in dogs and other species, and are transmitted mainly by ticks. Babesia are protozoal parasites that attack blood cells, though the severity of illness varies considerably depending on the species of Babesia involved, as well as the immune response of the infected dog.

The primary result of a Babesia infection is anemia as the immune system destroys infected red blood cells, but Babesia can have other effects throughout the body as well.

Cause

Babesia are a type of microscopic parasites that infect red blood cells, causing a disease called babesiosis. There are many species of Babesia, which infect a wide variety of animals, but there are only a few species that affect dogs. While our understanding of Babesia is improving, diagnosis and treatment of Babesia infections remains challenging.

Most Babesia infections are acquired through ticks. Because it is spread by ticks, Babesia is most common in warmer weather when ticks are most numerous. Infections are also possible through blood transfusions, and in the case of one Babesia species (Babesia gibsoni), dog-to-dog transmission via bite wounds is thought to be a mode of transmission. Mothers can also pass Babesia to their pups before birth.

Risk Factors

Babesia infections occur worldwide in areas where the ticks that carry the disease are common. While any dog can be infected, young dogs tend to suffer more serious illness. Greyhounds, pit bull terriers, and American Staffordshire terriers seem to be most susceptible to infection (Greyhounds with a strain of Babesia canis, and terriers with Babesia gibsoni).

Signs and Symptoms of Babesia

Babesia infections have a wide range of severity: they can be very mild (dogs may not even show symptoms) or very severe (sometimes fatal). The severity depends mainly on the species of Babesia involved but also on the immune system of the dog. The course of the disease may be cyclical, with periods of symptoms punctuated by times where symptoms are absent.

Signs and symptoms may include:

- fever

- weakness

- lethargy

- pale gums and tongue

- red or orange urine

- jaundice (yellow tinge to skin, gums, whites of eyes, etc)

- enlarged lymph nodes

- enlarged spleen

In severe cases, multiple organ systems may also be affected such as the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and the nervous system. Sometimes dogs suffer a very acute form of Babesiosis and suddenly go into shock and collapse.

Diagnosis of Babesia

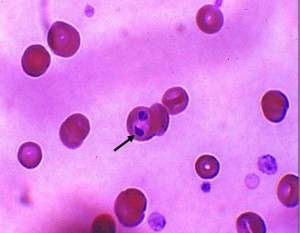

It can be difficult to confirm a diagnosis of Babesiosis. Blood tests may show a decrease in the number of red blood cells and platelets (thrombocytopenia), but this is not specific to Babesia. Blood smears can be examined for the presence of the Babesia organisms. If they are present, the diagnosis can be confirmed, but they may not always show up on a smear (taking blood from a cut on the ear tip or from a toenail can improve the odds of finding the parasites).

It can be difficult to confirm a diagnosis of Babesiosis. Blood tests may show a decrease in the number of red blood cells and platelets (thrombocytopenia), but this is not specific to Babesia. Blood smears can be examined for the presence of the Babesia organisms. If they are present, the diagnosis can be confirmed, but they may not always show up on a smear (taking blood from a cut on the ear tip or from a toenail can improve the odds of finding the parasites).

Blood can also be tested for antibodies to Babesia, though this can sometimes produce misleading results. Specialized testing can check for genetic material from Babesia, and while this is the most sensitive test, it is not widely available and has some limitations as well. Generally, a combination of lab tests along with clinical signs and history are used to make a diagnosis.

The diagnosis is further complicated by the fact that dogs infected with Babesia may also be infected with other diseases carried by ticks, such as Ehrlichia or Lyme disease.

Treatment of Babesia

A variety of drugs have been used to treat Babesia, with variable success. The drugs can have a range of side effects which can be quite severe. A newer combination of drugs, azithromycin and atovaquone, is promising, though expensive. In severe cases, blood transfusions may be necessary.

Treatment relieves the symptoms of babesiosis, but it seems that in many cases, it does not fully clear the parasite from the body. Dogs may remain infected at a low level, and Babesia can flare up again in times of stress or reduced immune function. Dogs that have been diagnosed with Babesia should not be bred or used as blood donors (to prevent spreading disease).

Prevention of Babesia

Preventing exposure to the ticks that carry Babesia is the best means of preventing babesiosis. Check your dog daily for ticks and remove them as soon as possible (ticks must feed for at least 24-48 hours to spread Babesia). This is especially important in peak tick season or if your dog spends time in the woods or tall grass (consider avoiding these areas in tick season).

Products that prevent ticks such as monthly parasite preventatives (e.g. Frontline) or tick collars (Scalibor) can be used, be sure to follow your veterinarian’s advice when using these products. Keep grass and brush trimmed in your yard, and in areas where ticks are a serious problem, you can also consider treating the yard and kennel area for ticks.

A vaccine is available in Europe, but is only effective against particular strains of Babesia and is not 100 percent effective.

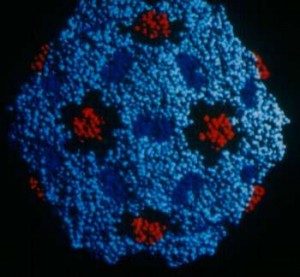

Canine parvovirus

What is canine parvovirus?

The canine parvovirus (CPV) infection is a highly contagious viral illness that affects dogs. The virus manifests itself in two different forms. The more common form is the

- intestinal form, which is characterized by

- vomiting,

- diarrhea,

- weight loss,

- and lack of appetite (anorexia).

The less common form is the

- cardiac form

- which attacks the heart muscles of very young puppies, often leading to death.

The majority of cases are seen in puppies that are between six weeks and six months old. The incidence of canine parvovirus infections has been reduced radically by early vaccination in young puppies.

Symptoms and Types

The major symptoms associated with the intestinal form of a canine parvovirus infection include severe,

- bloody diarrhea,

- lethargy,

- anorexia,

- fever,

- vomiting,

- and severe weight loss.

The intestinal form of CPV affects the body’s ability to absorb nutrients, and an affected animal will quickly become dehydrated and weak from lack of protein and fluid absorption. The wet tissue of the mouth and eyes may become noticeably red and the heart may beat too rapidly. When your veterinarian palpates (examine by touch) your dog’s abdominal area, your dog may respond with pain or discomfort. Dogs that have contracted CPV may also have a low body temperature (hypothermia), rather than a fever.

The intestinal form of CPV affects the body’s ability to absorb nutrients, and an affected animal will quickly become dehydrated and weak from lack of protein and fluid absorption. The wet tissue of the mouth and eyes may become noticeably red and the heart may beat too rapidly. When your veterinarian palpates (examine by touch) your dog’s abdominal area, your dog may respond with pain or discomfort. Dogs that have contracted CPV may also have a low body temperature (hypothermia), rather than a fever.

Causes

Most cases of CPV infections are caused by a genetic alteration of the original canine parvovirus: the canine parvovirus type 2b. There are a variety of risk factors that can increase a dog’s susceptibility to the disease, but mainly, the virus is transmitted either by direct contact with an infected dog, or indirectly, by the fecal-oral route. Heavy concentrations of the virus are found in an infected dog’s stool, so when a healthy dog sniffs an infected dog’s stool, it will contract the disease. The virus can also be brought into a dog’s environment by way of shoes that have come into contact with infected feces. There is evidence that the virus can live in ground soil for up to a year. It is resistant to most cleaning products, or even to weather changes. If you suspect that you have come into contact with feces at all, you will need to wash the affected area with household bleach, the only disinfectant known to kill the virus.

Improper vaccination protocol and vaccination failure can also lead to a CPV infection. Breeding kennels and dog shelters that hold a large number of inadequately vaccinated puppies are particularly hazardous places. For unknown reasons, certain dog breeds, such as Rottweilers, Doberman Pinschers, Pit Bulls, Labrador Retrievers, German Shepherds, English Springer Spaniels, and Alaskan sled dogs, are particularly vulnerable to the disease. Diseases or drug therapies that suppress the normal response of the immune system may also increase the likelihood of infection.

Diagnosis

CPV is diagnosed with a physical examination, biochemical tests, urine analysis, abdominal radiographs, and abdominal ultrasounds. A chemical blood profile and a complete blood cell count will also be performed. Low white blood cell levels are indicative of CPV infection, especially in association with bloody stools. Biochemical and urine analysis may reveal elevated liver enzymes, lymphopenia, and electrolyte imbalances. Abdominal radiograph imaging may show intestinal obstruction, while an abdominal ultrasound may reveal enlarged lymph nodes in the groin, or throughout the body, and fluid-filled intestinal segments.

CPV is diagnosed with a physical examination, biochemical tests, urine analysis, abdominal radiographs, and abdominal ultrasounds. A chemical blood profile and a complete blood cell count will also be performed. Low white blood cell levels are indicative of CPV infection, especially in association with bloody stools. Biochemical and urine analysis may reveal elevated liver enzymes, lymphopenia, and electrolyte imbalances. Abdominal radiograph imaging may show intestinal obstruction, while an abdominal ultrasound may reveal enlarged lymph nodes in the groin, or throughout the body, and fluid-filled intestinal segments.

You will need to give a thorough history of your pet’s health, recent activities, and onset of symptoms. If you can gather a sample of your dog’s stool, or vomit, your veterinarian will be able to use these samples for microscopic detection of the virus.

Treatment

Since the disease is a viral infection, there is no real cure for it. Treatment is focused on curing the symptoms and preventing secondary bacterial infections, preferably in a hospital environment. Intensive therapy and system support are the key to recovery. Intravenous fluid and nutrition therapy is crucial in maintaining a dog’s normal body fluid after severe diarrhea and dehydration, and protein and electrolyte levels will be monitored and regulated as necessary. Medications that may be used in the treatment include drugs to curb vomiting (antiemetics), H2 Blockers to reduce nausea, antibiotics, and anthelmintics to fight parasites. The survival rate in dogs is about 70 percent, but death may sometimes result from severe dehydration, a severe secondary bacterial infection, bacterial toxins in the blood, or a severe intestinal hemorrhage. Prognosis is lower for puppies, since they have a less developed immune system. It is common for a puppy that is infected with CPV to suffer shock, and sudden death.

Since the disease is a viral infection, there is no real cure for it. Treatment is focused on curing the symptoms and preventing secondary bacterial infections, preferably in a hospital environment. Intensive therapy and system support are the key to recovery. Intravenous fluid and nutrition therapy is crucial in maintaining a dog’s normal body fluid after severe diarrhea and dehydration, and protein and electrolyte levels will be monitored and regulated as necessary. Medications that may be used in the treatment include drugs to curb vomiting (antiemetics), H2 Blockers to reduce nausea, antibiotics, and anthelmintics to fight parasites. The survival rate in dogs is about 70 percent, but death may sometimes result from severe dehydration, a severe secondary bacterial infection, bacterial toxins in the blood, or a severe intestinal hemorrhage. Prognosis is lower for puppies, since they have a less developed immune system. It is common for a puppy that is infected with CPV to suffer shock, and sudden death.

Living and Management

Even after your dog has recovered from a CPV infection, it will still have a weakened immune system, and will be susceptible to other illnesses. Talk to your veterinarian about ways by which you can boost your dog’s immune system, and otherwise protect your dog from situations that may make it ill. A diet that is easily digested will be best for your dog while it is recovering.

Your dog will also continue to be a contagion risk to other dogs for at least two months after the initial recovery. You will need to isolate your dog from other dogs for a period of time, and you may want to tell neighbors who have dogs that they will need to have their own pets tested. Wash all of the objects your dog uses (e.g., dishes, crate, kennel, toys) with non-toxic cleaners. Recovery comes with long-term immunity against the parvovirus, but it is no guarantee that your pet will not be infected with the virus again.

Prevention

The best prevention you can take against CPV infection is to follow the correct protocol for vaccination.

Young puppies should be vaccinated at six, nine, and twelve weeks, and should not be socialized with outside dogs until at least two weeks after their last vaccinations. High-risk breeds may require a longer initial vaccination period of up to 22 weeks.